At 2 a.m. on Dec. 13, 2013, a Riviera Beach mom woke up to find her newborn baby’s lips were purple. Blood and milk oozed from the girl’s nose. She had stopped breathing.

The baby, authorities say, likely was accidentally smothered to death by her mother, who placed the girl in bed with her and three other children — a practice known as “co-sleeping” that can be lethal to infants. Child welfare investigators had been involved with the family four times before the infant’s death.

An investigator prepared an incident report on the baby’s death later that day and emailed it to a supervisor.

The paper trail ended there.

Kimberly Welles, an administrator at the Department of Children & Families’ Southeast Region, deleted the incident report, email records show. And she instructed the supervisor who wrote it, Lindsey McCrudden, to deep-six it, as well.

“Please do not file this in the system. No incident reports right now on death cases,” Welles wrote in an email that day. “Please withdraw this and thanks. Will advise why later.”

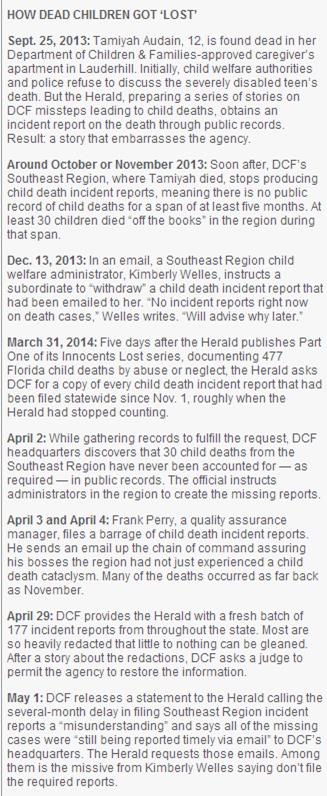

Last November, the Miami Herald was finishing a tally of Florida child abuse and neglect deaths among families that had previously come to the attention of DCF. The count was undertaken as part of a project called Innocents Lost. To track the number of dead children, which soared to new heights in recent years, reporters relied on public records, including incident reports.

Documents obtained after Innocents Lost was published show that starting at least as early as last November, as the Herald was grilling DCF on its problems in preventing the deaths of children under its watch, one branch of the agency deliberately kept as many as 30 deaths off the books — ensuring they would not be included in the published tally.

The incidents were in DCF’s Southeast Region, encompassing Palm Beach, Martin, St. Lucie, Okeechobee and Broward — the county cited by the Herald as having the most reported deaths by abuse or neglect.

DCF’s new secretary, Mike Carroll, said he has dispatched his top deputy, Pete Digre, to look into the missing records.

Carroll’s initial assessment of the matter: “Was it ill-advised? Absolutely. Was it a mistake? Absolutely.”

But as to whether the missing records amounted to a deliberate attempt to conceal deaths or suppress numbers in a series of articles highlighting DCF blunders, Carroll said: “I am not certain yet. I hope that’s not the case. I have made it clear to folks that we are not in the business of hiding information.”

Southeast Region administrators say they ceased filing the required reports for at least five months because they were in the process of developing a new reporting tool, Carroll said.

He added: “There is no evidence that makes me think there was a conspiracy to withhold information. … I don’t have anything that shows me this was done with ill intent.”

Carroll reaffirmed previous pledges to transform his agency into one of the most open and forthcoming in the United States, beginning with the online posting of “every single death report.” Streamlining and speeding up the availability of agency information, Carroll said, will not only allow DCF to quiet its critics — it may help the agency improve its performance.

“We have to get better at what we do,” Carroll said. “If DCF had contact with a child, we should have zero child deaths with those families.”

BEDSORES AND WOUNDS

The story of the Southeast Region’s phantom deaths likely begins at the end of September. That’s when Lauderhill police began an investigation into the death of 12-year-old Tamiyah Audain, whose emaciated and pockmarked body was found at the home of her DCF-approved caregiver. Diagnosed at birth with a rare genetic disorder, Tamiyah was wholly dependent on her young cousin for nourishment and medical care.

The Herald learned of the death through sources and sought details from DCF. Agency administrators refused to discuss it.

But an incident report describing Tamiyah’s final days later helped fill in the gaps. It was provided to the Herald in response to a public records request. The details were grisly: Though Tamiyah was supposed to be under the protective supervision of a private foster care caseworker, she had become mortally malnourished. Her body was covered with bedsores, one of them a crevasse deep enough to show her bone. Police described a “stench” that pervaded her caregiver’s home.

An autopsy concluded that both the cause and manner of Tamiyah’s death were undetermined. But it also detailed a pervasive infection, a healing rib fracture and multiple wounds and bedsores. The episode was deeply embarrassing to DCF, which was already reeling from a series of child deaths that had caused DCF’s top administrator to resign.

In the ensuing weeks, records show, child abuse investigators in the Southeast Region’s five counties ceased filing child death incident reports, which are required by DCF policies.

The missing incidents ran the gamut from gunshot deaths to accidental drownings to smotherings to a murder-suicide.

Meanwhile, the Herald published Innocents Lost — which detailed the deaths of 477 Florida children over a six-year period — starting March 26.

RASH OF DEATHS

In an effort to bring readers up to date, reporters on March 31 requested all child death incident reports statewide since Nov. 1, roughly when the Herald’s gathering of death reports had concluded. As the agency prepared to fulfill the records request, it discovered a strange new development: From at least November onward, the Southeast Region apparently had stopped filing incident reports, though more than two dozen child deaths had occurred in the region, according to the state’s child abuse and neglect hotline.

On April 2, a DCF child abuse and quality assurance specialist, Leslie Chytka, wrote in an email that she had found 30 child deaths with no corresponding incident reports — a violation of agency rules that say such reports must be completed “within one working day” of a child’s death. She instructed staff in the region to file reports for all of the 30 deaths.

That led to another email, from another staffer, with the title: “the upcoming rash of incident report deaths.” In it, DCF quality assurance manager Frank Perry wrote: “Disregard the next thirty or so incident reports that will be posted in the next day or so. They are child deaths we are aware of but are not in the … system. I have been asked to create these incidents so they are recorded.”

And create them he did — very quickly. The reports, filed by Perry on April 3 and April 4, are unlike any of the of the 145 or so the Herald received from the rest of the state at that time: They were largely devoid of information. Many of the Perry reports consisted of four sentences or fewer and offered no information, or scant information, regarding each family’s history with DCF. Such information is customarily provided in an incident report.

“[Redacted] was found in rigor mortis face down in the blankets where he slept,” Perry wrote in one report, neglecting to include a sentence-ending period.

“[Redacted] died from drowning in the pool at the home,” he wrote in another, also lacking final punctuation.

And another: “EMS responded to a call from the mother about her daughter, [redacted] being ‘non-responsive and not breathing.”

Only one child death incident report from the region included unredacted details of the family’s history with DCF. That one involved a November 2013 case in which an infant from Miami-Dade County was accidentally smothered by a relative in Broward. In the report, DCF administrators blamed the death on a Miami judge who ignored an agency recommendation about where the baby should live.

“A Miami judge overruled a negative homestudy,” DCF’s then-secretary, Esther Jacobo, wrote in an email that the Herald received later.

MANY PRIORS

MANY PRIORS

One of the incident reports filed on April 4 concerned the Jan. 25 smothering death of a Palm Beach County infant. Perry’s incident report described the case this way: “[Redacted] was found face down on a pillow not moving or breathing. The crib was not set up because there was no room.”

Manner of death, according to Perry’s report: accidental.

By the time Perry filed the report, however, agency administrators knew there was considerable evidence that was not true.

The incident report appears to correspond to a string of emails obtained by the Herald. In the discussion, the Southeast Region’s director, Dennis Miles, told DCF’s deputy secretary that the baby’s death was probably a homicide.

“Originally came in and appeared to be a [sudden infant death] type situation,” Miles wrote. “However,” he added, “children began stating that the father was seen smothering the baby with a pillow.”

As to DCF’s history with the family, Miles wrote: “Many priors.” Miles downplayed the significance of the agency’s involvement with the family by saying most of the prior investigations “are with different combinations of these parents and their ex’s.” The most recent investigation had occurred earlier in the year. Miles wrote that it was closed unverified — meaning not determined to be neglect or abuse — though family members were “uncooperative” with the investigation.

Welles, who apparently reviewed the case, wrote in an email that investigators “could have” considered seeking advice from agency lawyers a year earlier to determine whether the family should have been forced to accept help, or whether the children should have been removed from their parents.

The 8-month-old’s siblings were taken into state care following his death. “Kids safe,” Welles wrote on Jan. 26.

A GOOD MOTHER

One of the most puzzling incident reports concerned the Riviera Beach newborn who died on Dec. 13, 2013 — the report that Welles insisted be spiked.

Following requests from the Herald, DCF produced what it said was the report originally attached to McCrudden’s email. But it was contained in a format that does not match any of the hundreds of incident reports the Herald has reviewed in recent years. DCF later acknowledged that McCrudden — a nine-year DCF employee and supervisor since April 2013 — had “filled out the wrong form” — a document typically used for slip-and-falls at office buildings, or employee injuries.

The incident report given to the newspaper was unusual in other ways. It was not dated. And it contained no information on the family’s history with DCF, though such information is included in virtually all such documents.

A DCF spokeswoman later said the newborn’s parents had been the subject of four prior investigations, the most recent in 2011. A police report said a DCF complaint had been received last year. Three of the investigations involved allegations of family violence; the other was a report of substance abuse. None of the reports were verified as abuse or neglect.

The incident report described the baby’s mother and grandmother in glowing terms: “The mother is a good mother and takes really good care of the children.” The grandmother, it added, “is a great grandmother; she helps care for the children.”

The newborn was found dead after her mom placed her in bed along with herself and three other children, a 6-year-old, a 3-year-old and a 1-year-old. This manner of co-sleeping, considered especially dangerous, was linked to an estimated 77 of the 477 deaths reviewed by the newspaper in Innocents Lost. A little before 2 a.m., a police report said, the baby’s mom found her face “turned into” her mom’s chest. She was “bleeding from her nose, and her lips were purple.”

A report from the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office attributed the cause of the girl’s death to co-sleeping. The mother, the report said, rolled over the infant during the night, “causing her to suffocate.”